DBCI: Kerri Mumford and Jen Cree on Third Circuit Confirms No Triangular Setoff Under 553 Exception: ‘Mutual’ Means Mutual

In the July 21, 2021 edition of the Delaware Business Court Insider, LRC attorneys Kerri Mumford and Jennifer Cree write on Third Circuit Confirms No Triangular Setoff Under 553 Exception: ‘Mutual’ Means Mutual

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit recently issued a precedential decision involving a matter of first impression that likely will modify how pharmaceutical and other distributors and their related entities structure their business dealings with manufacturers and others with analogous arrangements.

By Kerri K. Mumford and Jennifer L. Cree

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit recently issued a precedential decision involving a matter of first impression that likely will modify how pharmaceutical and other distributors and their related entities structure their business dealings with manufacturers and others with analogous arrangements. In In re Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc., 990 F.3d 748 (3d Cir. 2021), the court affirmed the United States District Court for the District of Delaware and the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware decisions that held that Bankruptcy Code section 533 does not permit triangular setoffs because they lack mutuality.

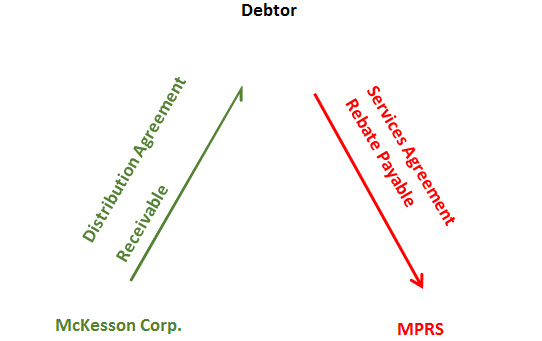

Prior to its bankruptcy filing, Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc. (“Orexigen”), a publicly traded pharmaceutical company that produced the weight management drug Contrave, entered into two agreements with two distinct but affiliated entities. The first was a distribution agreement (“Distribution Agreement”) with McKesson Corporation, Inc. (“McKesson”), wherein McKesson distributed products for Orexigen. The Distribution Agreement contained a provision that McKesson could set off amounts owed to Orexigen by any amount Orexigen owed to McKesson or any McKesson subsidiary (the “Setoff Provision”). The second agreement, for a consumer discount program administered through retail pharmacies (“Services Agreement”), was between Orexigen and McKesson Patient Relationship Solutions (“MPRS”), a McKesson subsidiary. Under the Services Agreement, MPRS advanced funds to pharmacies that sold Orexigen products, and Orexigen was obligated to reimburse MPRS for these services.

The Distribution Agreement and Services Agreement did not reference, incorporate, or integrate one another, and the parties agreed that McKesson and MPRS were distinct legal entities. During Orexigen’s bankruptcy case, Orexigen rejected, pursuant to Bankruptcy Code section 365, both the Distribution Agreement and the Services Agreement.

As of Orexigen’s bankruptcy filing, Orexigen owed MPRS approximately $9 million and McKesson owed Orexigen approximately $7 million. McKesson argued unsuccessfully before the bankruptcy court and the district court that it should be allowed to set off McKesson’s debt to Orexigen with MPRS’ claim against Orexigen under section 553 of the Bankruptcy Code. Both courts held that McKesson’s triangular setoff did not meet the strict mutuality requirements under Bankruptcy Code section 553, and McKesson could not contract around the mutuality requirement.

To invoke the setoff exception under section 553 of the Bankruptcy Code, a creditor must have a right to set off debt under state law. The Third Circuit, in United States ex. rel. IRS v. Norton, 717 F.2d 767 (3d Cir. 1983), held that section 553 of the Bankruptcy Code is not an independent source of setoff law; it is better understood as preserving a right created by state law to set off debt. However, the preservation of a state law setoff right is not absolute against a bankrupt entity: it does not circumvent the express requirement of mutuality in section 553 of the Bankruptcy Code. Orexigen and McKesson agreed for purposes of argument that California law (the governing law under the Distribution Agreement and Services Agreement) provided a state law setoff right.

Bankruptcy Code section 553 provides that

[e]xcept as otherwise provided in this section and in sections 362 and 363 of this title, this title does not affect any right of a creditor to offset a mutual debt owing by such creditor to the debtor that arose before the commencement of the case under this title against a claim of such creditor against the debtor that arose before the commencement of the case[.]

11 U.S.C. § 553(a). In other words, a creditor with a state law setoff right can set off amounts it owes to a debtor against amounts that the debtor owes to it. However, in this case, McKesson owed Orexigen amounts due under the Distribution Agreement and Orexigen owed MPRS amounts due under the Services Agreement.

Accordingly, the bankruptcy court rejected McKesson’s argument that it could set off its amounts due to Orexigen under the Distribution Agreement against Orexigen’s amounts due to MPRS under the Services Agreement, holding that while the Setoff Provision constituted an “enforceable contractual right allowing a parent and its subsidiary corporation to [e]ffect a prepetition triangular setoff under state law[,]” that relationship “does not supply the strict mutuality required in bankruptcy.” In re Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc., 596 B.R. 9, 12 (Bankr. D. Del. 2018). The district court affirmed the bankruptcy court’s decision. In re Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 697 (Del. Jan. 3, 2020).

Accordingly, the bankruptcy court rejected McKesson’s argument that it could set off its amounts due to Orexigen under the Distribution Agreement against Orexigen’s amounts due to MPRS under the Services Agreement, holding that while the Setoff Provision constituted an “enforceable contractual right allowing a parent and its subsidiary corporation to [e]ffect a prepetition triangular setoff under state law[,]” that relationship “does not supply the strict mutuality required in bankruptcy.” In re Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc., 596 B.R. 9, 12 (Bankr. D. Del. 2018). The district court affirmed the bankruptcy court’s decision. In re Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 697 (Del. Jan. 3, 2020).

McKesson raised two issues in its appeal to the Third Circuit: (1) whether the meaning of the term “mutual” in Bankruptcy Code section 553 operates as a distinct statutory requirement for effectuating setoff rights, and (2) if so, whether state contract law can provide an exception to the requirement of direct mutuality. The Third Circuit recognized that the former issue had been settled in the affirmative among its sister circuits; however, the latter issue had not been addressed by other circuits.

Just as the bankruptcy court and the district court had done, the Third Circuit analyzed what Congress meant by “mutual” in section 553. Orexigen argued that strict bilateral mutuality is required (i.e., creditor-debtor; debtor-creditor); while McKesson argued that “mutual” should not be intended as limiting state law contractual setoff rights. The Third Circuit adopted “the well-reasoned” analysis that Congress intended for mutuality to mean only debts owing between two parties: specifically, those owing from a creditor directly to the debtor and, in turn, owing from the debtor directly to that creditor, explaining that “Congress did not intend to include within the concept of mutuality any contractual elaboration on that kind of simple, bilateral relationship.” The Third Circuit also rejected McKesson’s argument that its parent-subsidiary relationship with MPRS created bilateral mutuality because the right to set off under Bankruptcy Code section 553 is personal and “quite literally is tied to the identity of a particular creditor that owes an offsetting debt.”

The Third Circuit observed that this conclusion is consistent with the Bankruptcy Code’s general policies of equality among creditors and that setoff rights (allowing payment in full of a prepetition claim) must be strictly construed. The court also observed that adopting McKesson’s interpretation of Bankruptcy Code section 553, where contractual setoff agreements can “shoehorn multiparty debts into [section] 553, would disincentivize public disclosure of prioritized claims” and “weaken[] a fundamental purpose of the [Bankruptcy] Code.”

The Third Circuit also soundly rejected McKesson’s argument that its right to set off was a “claim” under the Bankruptcy Code. The court found McKesson’s attempt to view the term “claim” in isolation distorted Bankruptcy Code section 553’s meaning, noting “[t]rying to offset a debt against a setoff right [as opposed to a claim] strikes us as nonsense.” At bottom, the Third Circuit’s decision establishes that mutuality in the context of Bankruptcy Code section 553 requires a bilateral relationship between entities, and an entity cannot contractually manufacture mutuality vis-à-vis a third party.

However, the court offered potential practical solutions for companies involved in these multi-entity arrangements to ensure payment. For example, McKesson could have taken on directly the retail pharmacy support MPRS had handled. Alternatively, the court observed that MPRS could have perfected a security interest in Orexigen’s account receivable due from McKesson, which may have altered the priority status of the amount McKesson sought to set off and put Orexigen’s other creditors on notice in advance of its secured claim.

The decision ultimately offers guidance for parties transacting business and contracting with pharmaceutical manufacturers and other entities that enter into similar multi-entity arrangements regarding the priority of their claims in the event of bankruptcy of one entity.

Reprinted with permission from the July 21, 2021 issue of the Delaware Business Court Insider. © 2021 ALM Media Properties. Further duplication without permission is prohibited.